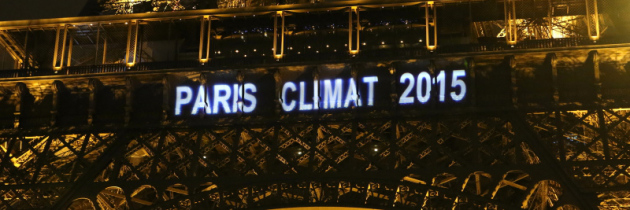

The Tough Realities of the Paris Climate Talks

IN less than a month, delegates from more than 190 countries will convene in Paris to finalize a sweeping agreement intended to constrain human influence on the climate. But any post-meeting celebration will be tempered by two sobering scientific realities that will weaken the effectiveness of even the most ambitious emissions reduction plans that are being discussed.

The first reality is that emissions of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas of greatest concern, accumulate in the atmosphere and remain there for centuries as they are slowly absorbed by plants and the oceans. This means modest reductions in emissions will only delay the rise in atmospheric concentration but will not prevent it. Thus, even if global emissions could be reduced by a heroic average 20 percent from their “business as usual” course over the next 50 years, we would be delaying the projected doubling of the concentration by only 10 years, from 2065 to 2075.

Unconditional national commitments made by countries for the Paris meeting are projected to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions through 2030 by an average of only 3 percent below the business-as-usual average rise of 8 percent.

This is why drastic reductions would be needed to stabilize human influences on the climate at supposed “safe” levels. According to scenarios used by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global annual per capita emissions would need to fall from today’s five metric tons to less than one ton by 2075, a level well below what any major country emits today and comparable to the emissions from such countries as Haiti, Yemen and Malawi. For comparison, current annual per capita emissions from the United States, Europe and China are, respectively, about 17, 7 and 6 tons.

The second scientific reality, arising from peculiarities of the carbon dioxide molecule, is that the warming influence of the gas in the atmosphere changes less than proportionately as the concentration changes. As a result, small reductions will have progressively less influence on the climate as the atmospheric concentration increases. The practical implication of this slow logarithmic dependence is that eliminating a ton of emissions in the middle of the 21st century will exert only half of the cooling influence that it would have had in the middle of the 20th century.

These two scientific realities make emissions reductions a sluggish lever for constraining human influences on the climate. At the same time, societal realities conspire to make emissions reductions themselves difficult. Energy demand, which is strongly correlated with rising incomes and living standards, is expected to grow by some 50 percent by midcentury, driven by economic progress in developing countries and by population growth to about 9.7 billion people from the current 7.3 billion.

Read more on The New York Times