Sticking points remain over climate talks in Paris

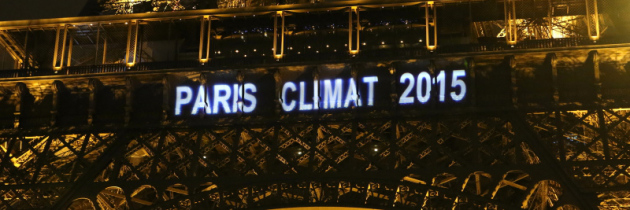

A day after most of the world’s leaders delivered a powerful call for action to stop global warming, the challenge of turning their rhetoric into a new climate accord has become painfully clear. Negotiators from the 195 countries taking part in UN talks in Paris confronted a host of divisive issues on Tuesday as they began work trying to convert an unwieldy draft text into a crisp agreement for ministers to finalise next week.

These are five of the biggest sticking points.

1. How soon should countries’ have to beef up their emissions reduction targets?

This is shaping up to be one of the most difficult issues.

All but a handful of the 195 countries involved have published climate strategies for the accord, but these do not add up to enough collective action to avert dangerous levels of global warming.

The EU and many smaller developing countries say it is therefore imperative for the agreement to require countries to do a stocktake of the impact of their combined action every five years, and then ratchet up their targets as early as 2020.

Agreement is broad that a stocktaking review should be done every five years. But India, China and several countries in Latin America and the Middle East want to wait until up to 2030 to strengthen their targets, a date other nations say is far too distant.

Developing countries also say they should be allowed to wait longer than wealthy ones to toughen their targets, or only do so if they receive financial support from richer countries, measures those industrialised countries are resisting.

India, the world’s fourth-largest emitter after China, the US and the EU, insists developed nations have a historic responsibility to do more.

“Climate change is not about per capita incomes, it is about a share of historical emissions,” a spokesman for India’s delegation, Ajay Mathur, told reporters on Tuesday.

2. How much money should wealthy countries agree to pay developing countries to deal with global warming?

Developing countries want the accord to require rich countries to meet a previously agreed pledge to deliver $100bn a year by 2020 of climate finance to less advanced countries and larger sums after that.

The EU and the US are wary about including specific sums in an agreement that is supposed to last for decades.

They want the accord to acknowledge that some formerly poor countries are growing fast and either will not need climate finance in future or will start providing it themselves.

India appears to have accepted the $100bn figure will probably not appear in the final accord.

However, Mr Mathur said any climate finance that developing countries might offer in future would be purely voluntary and this was “very different from it being part of a final agreement”.

Brazil’s negotiators echoed this view on Tuesday, saying any funding developing countries might offer in future would done only on “a voluntary basis”.

Read more on Financial Times