Global warming doubles growth rates of Antarctic seabed’s marine fauna – study

Marine life on the Antarctic seabed is likely to be far more affected by global warming than previously thought, say scientists who have conducted the most sophisticated study to date of heating impacts in the species-rich environment.

Growth rates of some fauna doubled – including colonising moss animals and undersea worms – following a 1C increase in temperature, making them more dominant, pushing out other species and reducing overall levels of biodiversity, according to the study published on Thursday in Current Biology.

The researchers who conducted the nine-month experiment in the Bellingshuan Sea say this could have alarming implications for marine life across the globe as temperatures rise over the coming decades as a result of manmade greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Gail Ashton of the British Antarctic Survey and Smithsonian Environmental Research Center said she was not expecting such a significant difference. “The loss of biodiversity is very concerning. This is an indication of what may happen elsewhere with greater warning.”

Sub-zero conditions near the south pole mean there are comparatively few species on the usually frozen land, but below the ice, the relative lack of pollution, traffic and fishing has left an abundance of marine life that divers and biologists compare to coral reefs.

Previous studies of warming impacts have focused on single species, but the latest research examines an assemblage of creatures.

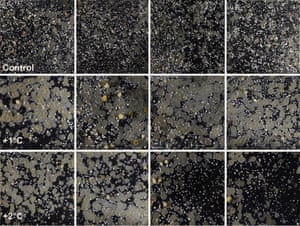

Twelve identical 15cm sq heat plates were set in concrete on the seabed. Four were warmed by 1C, four by 2C and four left at ambient temperature as a control.

At 1C, a species of bryozoan moss (Fenestrulina rugula) became utterly dominant on the four plates. Within two months it reduced the evenness and diversity of the species spread. The researchers also found the marine worm Romanchella perrieri grew an average 70% larger than those under ambient conditions.

At 2C, the results from different plates varied with different growth rates of different species. The researchers speculate that this may be because the higher increase in temperature had a greater shock impact.

Ashton said further longer-term studies should be conducted but the overall trend was already clear. “The indication of change being more than anticipated is fairly reliable. This is the best data we have to date.”

Until recently, most of the coverage of temperature rises has focused on the north pole, where the shrinking of arctic ice has been most visibly dramatic. But concerns are growing about the impact of global warming on the far bigger southern ice cap.

Earlier this year, the United Nations weather agency announced that temperatures in the Antarctic recently hit a record high.

An Argentine research base near the northern tip of the continent recorded a balmy 17.5C in March 2015, the World Meteorological Organisation revealed.

The vast continent contains 90% of the world’s fresh water, most of it locked in ice that is several kilometres thick. The effects of climate change are not uniform, but concerns grew in July when a trillion tonne block of the Larsen C ice shelf collapsedinto the sea.

The region is also steadily turning greener due to the increased growth of surface moss. UK-based scientists published a paper in May showing that growth rates of moss have accelerated more than fourfold since 1950.

The latest study suggests the trend could become more evident on the sea bed as well as the land surface.

Fonte: The Guardian