Notes from the undergrowth

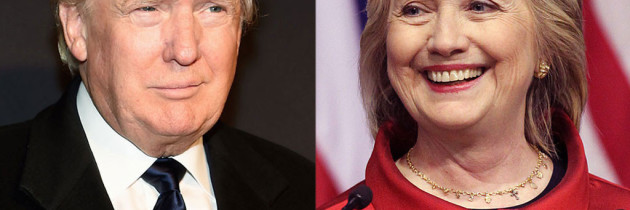

Despite, deluges in the South, droughts in the West and fires throughout national forests this year, the words “climate” and “change” have seldom been uttered together on the campaign trail. Fifteen of the 16 hottest years on record have occurred since 2000. Yet Donald Trump has claimed that global warming is a Chinese hoax designed to thwart American businesses (he also denied saying so at the first debate between the candidates, on September 26th). Hillary Clinton believes that “climate change is real” and that dealing with it will create jobs in the renewable-energy sector. In sum, the two candidates offer completely different environmental platforms.

Uncoupling emissions growth and economic expansion is important to slowing climate change. Total energy consumption in America has dropped 1.5% since Barack Obama became president, according to the White House; in that time the economy has swelled by 10%. America now generates more than three times as much electricity from wind, and 30 times as much electricity from solar, as it did eight years ago.

Most voters accept that climate change is happening. But Republicans and Democrats disagree as to why, according to the Yale Programme on Climate Change Communication, a research group. Half of Mr Trump’s supporters reckon natural causes explain it, whereas three in four of Mrs Clinton’s backers say, with almost all climate scientists, that man-made emissions are to blame.

In 2015 the most robust deal yet on curbing global carbon emissions emerged. The Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to “well below” 2ºC above pre-industrial temperatures. For its part, America promised to lower its emissions of carbon dioxide by 26-28% by 2025, as measured against the levels of 2005.

An important step to achieving this goal was unveiled last year: the Clean Power Plan. This proposes the country’s first national standards to limit carbon-dioxide emissions from power plants—America’s largest source of greenhouse gases. Legal challenges from fossil-fuel groups and two dozen mostly Republican-led states saw the Supreme Court put it on hold eight months ago. Some opponents argue the plan is unconstitutional; far stronger claims are made that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is overstepping its remit. Hearings on the plan began on September 27th. Whatever the outcome, the EPA retains the right to regulate carbon dioxide: the justices ensured that by declaring it a pollutant in 2007.

This is one area where Mrs Clinton is running for a third Obama term. She intends to make America a “clean energy superpower” by speeding up the process of greening that Mr Obama began. Within four years she wants half a billion solar panels installed, and by 2027 she plans for a third of electricity to come from renewables. Mrs Clinton laments that poorer areas are often the most polluted—citing, for example, the filthy water in Flint, Michigan. States and cities which build greener infrastructure, such as more thermally efficient buildings, will get handouts worth $60 billion. Mrs Clinton is vague about how she would pay for this, but slashing fossil-fuel subsidies could be part of the answer. Such handouts came to nearly $38 billion in 2014, according to Oil Change International, a research outfit, though estimates vary wildly.

Green types argue that such ambitious plans are possible. But since America is already lagging on its climate pledges for 2025, according to a study just published in Nature Climate Change, such optimism appears misplaced—especially as Mrs Clinton has no plans either to price or to tax carbon. In this she has learned from Mr Obama’s failures. His attempt to pass a cap-and-trade bill floundered in 2010, and he has tried to avoid Congress on environmental issues ever since. The Clean Air Act of 1963, for example, supposedly underpins the Clean Power Plan, allowing him to dodge the Senate. Mr Obama has also used his executive authority to ratify the Paris climate deal and to create the world’s largest protected marine area off Hawaii.

Mrs Clinton may follow suit with environmental executive actions of her own, according to hints from her campaign chief, John Podesta, Mr Obama’s environmental mastermind. She may seek to regulate methane leaking from existing gas installations and to tighten fuel-efficiency standards.

But what one president enacts, the next can challenge. Mr Obama’s penchant for executive action leaves the door open for Mr Trump to stall and perhaps reverse environmental policies if he becomes president. His intention to rip up the Paris Agreement will prove hard to carry out in a single term, however: it comes into force before January, and untangling America from its provisions could take around four years. Mr Trump favours oil and gas production on federal lands and opening offshore areas to drilling. He also plans “a top-down review of all anti-coal regulations”. Such moves could imperil the Paris deal anyway. If the world’s second-largest polluter shirked its pledges to cut emissions, many other countries would wriggle out of theirs.

Either candidate, as president, would be at the mercy of the markets. A glut of fossil fuels means that coal production has declined by almost a quarter since the highs of 2008. Improvements in fracking technology may see American shale output stabilise, and perhaps even grow, if it allows firms to compete more efficiently with rivals in Saudi Arabia. But the cost of solar and wind power, and of the storage needed to smooth out their variations, will keep dropping. If Mr Trump becomes president, energy firms may reduce emissions anyway. If Mrs Clinton does, they may give her green policies a needed boost.